IVL in the Left Main Q&A with Dr. James Spratt

Recently, Dr. James Spratt, consultant cardiologist at St George's University NHS Trust in London and founder of Optima Education, and other leading UK cardiologists published their experience with Intravascular Lithotripsy (IVL) in the left main in EuroIntervention: Intravascular lithotripsy for the treatment of calcific distal left main disease.

We had the privilege of connecting with Dr. Spratt to learn more about his publication and get some of his key takeaways as one of the most prolific IVL users since the introduction of the technology nearly two years ago:

Question: What concerns or considerations do you have about modifying calcium in the left main?

Dr. Spratt: The limitations in percutaneous treatment of the left main nearly always come down to the ability to achieve a certain size or volume in three key areas; one being the ostium of the LAD; second being the ostium of the circumflex; and the third area being called the polygon of confluence, which is basically where the LAD and the circumflex join into the distal end of the left main.

Normally, plaque is relatively compliant, so it can be shifted out of the way or stretched with balloon treatment. Calcium, however, is not compliant, and therefore not possible to shift it out of the way with just balloon treatment.

Prior to IVL, the only real significant tool we had to modify calcium was rotational atherectomy. The limitation with rotational atherectomy is first of all, the procedure in the left main can be especially hazardous because of the risk of distal no-reflow, but also, rotablation can’t work on lesions that it can’t ablate or touch. Therefore, if the lesion is not tight enough so that the burr doesn’t touch the lesion, then it doesn’t ablate it.

So prior to the development of IVL, while we could identify calcium, there was very little that we could do to modify it, particularly if it was deep-wall calcium.

Question: How does calcium most often present itself in the left main from your experience? Is it more proximal? More distal? Looking at that area in confluence, is it usually concentric or eccentric?

Dr. Spratt: Calcium is much more common in the bifurcation than the LMS shaft or ostium. Most of that is due to flow dynamics. Again, if you look at the bifurcation itself, the disease is more likely to be not at the carina, essentially the middle of the trousers of the two arteries, but at the sides. So as general rule, disease is more common at the bifurcation ~ 80% of total disease.

In terms of drilling down to the real granularity of looking at eccentricity versus concentricity, there really isn’t a lot of data to guide the answer. To date, it’s been primarily driven by anecdotal experience.

Question: What were your study’s goals – what did you seek to understand going into the research?

Dr. Spratt: The main goal of the study was to do two things, one to demonstrate feasibility in treating highly calcific lesions in patients who often didn’t have an alternative revascularization strategy and in whom previously only medical therapy was an option. And we knew that in that group, if they’re not treated with revascularization, they actually do very badly. So our goal was to demonstrate that they could be safely and effectively treated.

We understand the limitations of reporting a technique without any randomization, but nevertheless, given the novel nature of the technology and the importance of the topic, we felt that we could add value by reporting a relatively large number of patients with good results in 100% in patients of which, I would say, estimated 70 or 80% we would have no alternative form of treatment just one year ago.

Question: What were your study’s findings?

Dr. Spratt: The first thing to say is that we have very good surrogate markers of what constitutes the success for percutaneous revascularisation in the left main stem (LMS), and it’s not just looking at an angiogram and saying that looks good or that doesn’t look good. Unfortunately patient level experience isn’t granular enough to tell you how durable the result is likely to be. So, in other words, you can’t ask a patient how they feel the day after procedure and expect that to be a good guide of how they’ll feel in three or six months or a year or five years.

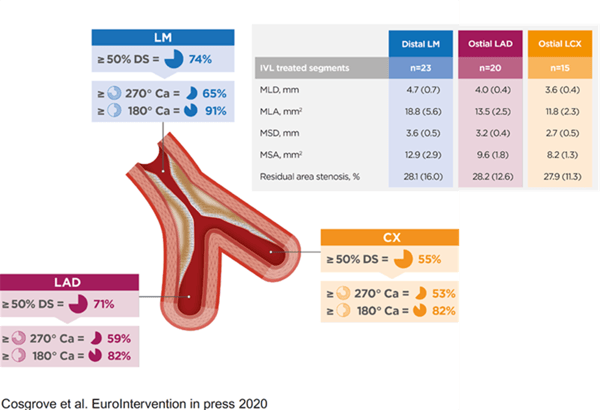

However measurements at the end of the procedure can be extrapolated to outcomes as far out as five years from now. Those measurements are very simply volume measurements or at least area measurements at the three critical areas: the LAD ostium, the circumflex ostium, and that polygon of confluence where the LM stem meets the LAD and circ. So one of our major goals was to show that in very severe calcific disease we could get areas there which we could extrapolate and predict a good three to five-year outcome for these patients.

And actually, even within our relatively small study, despite the fact that we were treating very severe disease, the average numbers we got in these areas with lithotripsy were actually higher than in both the two main left main stem papers published recently, NOBLE and EXCEL. So that was a major finding. (See graphic below for detailed area measurements.)

And the second major finding is that we could do that safely. There had been some considerations raised about the safety of prolonged balloon inflation in the left main stem that’s a necessary part of lithotripsy treatment. But we were fine, we were able to deliver lithotripsy without any complications whatsoever. And in the vast majority of our patients, they were able to be discharged the same day. And all of the patients have kept well since.

Question: What further research needs remain regarding IVL in the LM?

Dr. Spratt: When introducing new technology, the first thing to demonstrate is safety. I think there’s an increasing body of evidence that lithotripsy is safe, but while safety is good and important, it’s not enough on its own. The second step is efficacy. You want to be sure that it’s efficacious. So I think within a very small number of patients, it was safe and efficacious. But for it to become standard of care, it’s going to need more evidence than we have currently.

So at present there’s good evidence that if you don’t have an alternative good revascularization strategy in somebody with highly calcific left main disease, and that alternative would be bypass surgery, then this works very well and it’s safe and it’s relatively straightforward to use.

And I think we must all be very careful and not too overreaching in what we claim from what is a relatively small study. I think it’s a positive result. It’s given us encouragement to push forward. And I think we will be looking to follow it up with a more robust reflection of what lithotripsy can deliver in this environment.

Question: Based on your personal use, are there any best practices that you’ve identified when using IVL in the left main that leads to a more efficacious result?

Dr. Spratt: Within my practice, which consists mostly of surgical turndowns, CTOs, and post-bypass CTOs, it’s very straightforward technology to use. I think it’s best complimented by an appreciation of where best to apply it. I think that’s best achieved by intravascular imaging.

And again, it’s best applied where the goal is fairly clear. And I think the left main is one of the clearest areas where if you achieve certain imaging defined goals, you can be very confident in what you tell your patient about the success of the procedure.

My advice to fellow interventionists would be carefully assess where you’re going to need IVL. You don’t want to use it in every patient. After you have used it, carefully assess the cracked calcium by intravascular imaging. Finally, once the stent has been implanted, carefully assess that you’ve achieved the goals that you set yourself out at the start, that you’ve got those three key measurements that you were aiming for. And then once you’ve done all that, then you can tell the patient with confidence that they should keep well for a long period of time.

Question: How do you size your IVL catheter in the LM, especially when you have a larger LM?

Dr. Spratt: As you will be aware the maximum size of IVL balloon is 4mm and the recommended sizing is 1:1 - it is extremely rare that this will fail to appose in the body of the LMS (even in a very large vessel due to the fact that the lesion is quite stenosed) & will be appropriately sized in the daughter vessels. If the vessel is above 5.0mm, one might consider using a 1:1 RVD-sized NC balloon after IVL to further open up the vessel after the calcium has been fractured to maximize lumen gain before stent implantation.

Important Safety Information - Coronary

Caution: In the United States, Shockwave C2 Coronary IVL catheters are investigational devices, limited by United States law to investigational use. DISRUPT CAD III Study

Shockwave C2 Coronary IVL catheters are commercially available in certain countries outside the U.S. Please contact your local Shockwave representative for specific country availability. The Shockwave C2 Coronary IVL catheters are indicated for lithotripsy-enhanced, low-pressure balloon dilatation of calcified, stenotic de novo coronary arteries prior to stenting. For the full IFU containing important safety information please visit: https://shockwavemedical.com/clinicians/international/coronary/shockwave-c2/